How I Brew Coffee

Like many programmers, I like coffee…a lot. So, I thought I’d share a quick note on my process for brewing coffee.

TL;DR: it’s Tetsu Kasuya 4:6 pour over method. This video from the barista himself is a great demonstration.

The most remarkable thing about this method is how extremely consistent it is at getting really good, smooth coffee.

This opened up a huge world of coffee flavors to me, because once I could consistently brew good tasting coffee, I could then start to feel the difference between different roasts.

So, let’s me explain what the 4:6 method is all about.

The Method

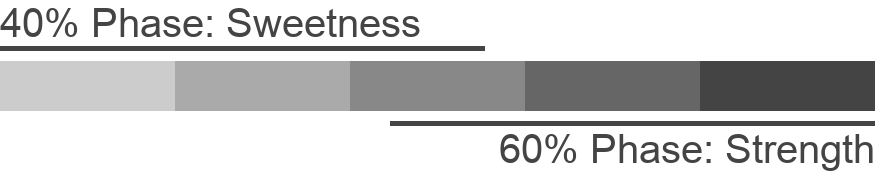

In the 4:6 method you typically use 5 pours, where the first 40% (ie. 2 pours) control the sweetness and the other 60% (ie. 3 pours) control the strength.

To start, you’ll need a few things: a pour over, burr grinder, a mug or carafe, scale, and timer.

This method uses 1g of ground coffee for each 15g of water. So take the amount of coffee you’d like to end up with. Then, divide that by 15 to get the amount of ground coffee beans to use.

Use a medium grind setting on your burr grinder to grind your coffee. A good grinder is important as explained below.

Bring the water up to temperature, around 195-205F. Now you’re going to do your first pour. In this method, you divide the total coffee by 5 to get the amount for each pour.

When pouring, pour quickly but smoothly moving in a circular motion to wet all the beans. Then, wait 45 seconds between pours.

Repeat these steps of pouring and waiting until you’ve done all 5 pours.

Flavor Profiles

Here is the typical profile with equal amounts for all 5 pours:

This makes a consistently good cup of coffee. But we can adjust it by changing the ratio or number of pours.

The 40% phase controls the sweetness and the 60% phase controls the strength.

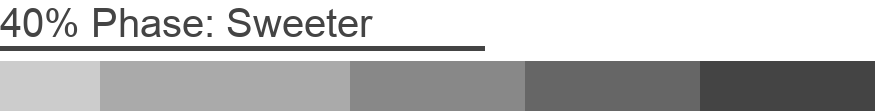

In the 40% phase, you can make the coffee sweeter by shortening the first pour relative the second. Lengthening it makes it more acidic.

Coffee beans need to off-gas a bit before extracting well. This is the puff you see when you first pour the water onto the coffee.

So, a smaller first pour “warms up” the beans, leading to more extraction in the longer second step.

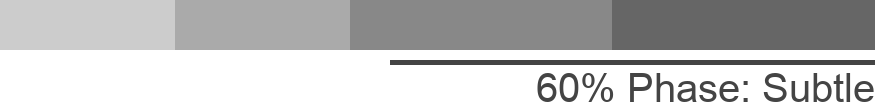

Similarly, in the 60% phase shorter pours lead to a stronger flavor. By default you would do 3 pours. 4 pours leads to extra strong coffee, whereas 2 pours lead to a more subtle flavor.

Shorter pours are stronger because they agitate the coffee more, leading the water to linger longer, brewing more.

But beware: changes to the 60% / strength phase will have a much larger impact on the resulting coffee.

Lots of Coffee

One of the benefits of this method is that you can brew up to 4 cups of coffee if you have a large enough pour over.

Typically, I brew with 40g coffee, 600g of water, and 120g per pour (when using the normal/equal distribution). That’s a bit over 2.5 cups of coffee.

But I made a cheatsheet that hangs on my fridge. This way I know whenever I have guests over and want to make a particular number of cups:

| Cups | Coffee | Total Water | Pour Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 15g | 255g | 45g |

| ~1.5 | 24g | 360g | 72g |

| 2 | 30g | 450g | 90g |

| ~2.5 | 40g | 600g | 120g |

| 3 | 45g | 675g | 135g |

| 4 | 63g | 945g | 189g |

The half cups (ie. 1.5, 2.5) are a bit generous, because real half cups make

for unwieldy sizes in grams since there is 236.588g per cup.

Grind Size & Ratio to Water

One area that I haven’t researched much yet with this method is grind size and the ratio of grinds to water.

Here, I’ve just stuck with the basic advice of using medium grind size and 1:15 ratio of coffee to water.

I’ve heard that you should use both more coffee and coarser grind sizes when brewing with larger amounts of coffee.

That jives with what I’ve experienced. Later pours in this method take longer. My understanding is that this is because finer grains of coffee start to clog the filter.

So for large batches that take a while to brew, grind size is important. And to compensate for larger grinds, you need more of them to keep the extraction at the right level.

Thus, you need a good burr grinder. Consistency in grind size is important for the later pours to prevent over-extraction.

This post from Coffee Ad Astra has a deep dive into grind size and consistency. He even made an app using computer vision to check grind sizes for yourself!

Conclusion

The 4:6 method is decently complicated. I’ve made some personal cheatsheets and scripts to help automate the timing and figuring out the distributions.

But it works so well that it’s worth it. It’s a very forgiving way to make consistently good coffee.

That said, there are still some areas that I’d like to learn more about, specifically grind size and ratio to water.

I have a Hario Skerton Plus for camping and a Baratza Encore in the kitchen at home.

These are both solid burr grinders. So, nailing the grind size is an are that I could explore more.

But until then, I’ll leave you with a final recommendation to give this method a try. It takes a bit of time to get used to. But the cheatsheets help.

And, it works excellently. So try making your next coffee this way and I think you’ll be pleasantly surprised.